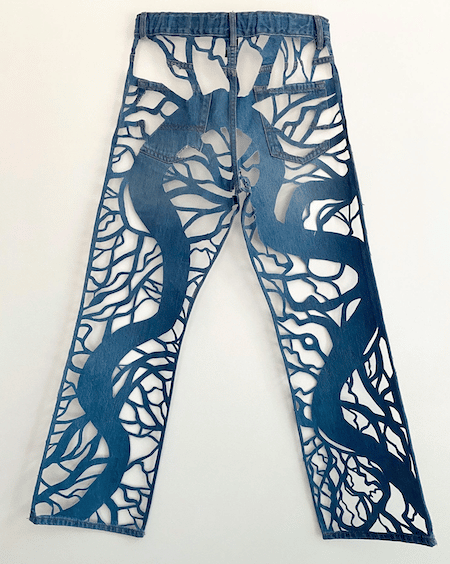

I didn’t realize that denim jeans were so damaging to the environment until I saw

Libby Newell’s sustainable art on the walls of a gallery.

The cotton plant consumes a lot of water, and then the process of dying the jeans — including any specialty washes— is reliant on soaking the cloth, then washing it several times in order to achieve a desired “lived-in” or distressed look. That water is often dumped back into the environment with harmful chemicals. If you consider that jeans are considered a wardrobe necessity and are purchased by many people all over the globe, this issue becomes very large and one that the apparel industry is probably not going to advertise.

In this case, it takes a person who is curious about the process and dedicated to making art about sustainability to bring this fact to our attention. Newell is an artist who would like us to know more about jeans’ impact on the environment, and she captures our attention with signature visual flair.

Newell quotes these facts when talking about her cut-jean piece, “Meticulously Distressed Denim, Death”:

“In order to construct a single pair of jeans, it can take up to 11,000 liters of water, much of which is contaminated with chemicals used during the dyeing process. These contaminated waters are unusable thereafter and are released back into the environment, thus, creating an unhealthy environment for wildlife and humans alike.”

Additionally, Newell states that “We can’t only focus on the environment under our own feet. We have to pay attention to the environmental impact of the shoes on our feet, the clothes on our bodies.”

Artist Libby Newell highlights the environmental perils that go into one of the most common garments in the world: blue jeans.

The environment is a focus of Newell, as she states in her artist statement. “Throughout her adult life, Libby has become increasingly aware of the disconnect between the clothing we constantly feel the need to purchase, the origin of these products, and the waste we create. By transforming discarded clothing and fashion and beauty magazines into objects using slow, thoughtful processes, she aims to encourage the viewer to slow down enough to consider and rethink their consumption habits.”

And thank goodness she does! I didn’t realize that jeans had such a negative impact on the environment, and now I will look for a denim company dedicated to sustainable water usage. The reason why I will change my purchasing habits is because I saw Libby Newell’s sustainable art jeans at an art exhibition.

Sustainable art illuminates substantial issues

In sustainable art, artists bring attention to the most pressing issues of our time, whether in their practice, over a body of work or in a single, arresting image.

Artists are uniquely positioned to offer up their perspectives in thought-provoking ways. They often practice sustainable art in two ways: by making art with sustainability as the subject of their artwork or by establishing a process that incorporates sustainable materials and techniques. Some artists do both!

Sustainable art practices can literally show us the way to make our own lives more earth-friendly and more in line with our personal values.

Another excellent example of a sustainable artist who has created a visual language to highlight an environmental issue is

Bryan Northup and his message about single-use plastics.

Northup says, “I started working with single-use plastic in 2015, witnessing that at the time, disposable plastic was a relatively ‘invisible problem’, I wanted to get plastic in front of people in an unexpected way, in the context of fine art, as a painted surface.”

Northup has a brilliant method of getting us to pay attention to single-use plastics: he uses them as a medium to create assemblage wall hangings that resemble sushi rolls, a nod to our “consumption” of plastic.

Bryan Northup’s sustainable art uses foraged single-use plastic to bring attention to the amount of plastic that pollutes our environment.

Northup writes: “We don’t really see plastic anymore, so I’m trying to reimagine it or present it for others to reimagine. Material and its manipulation are scrutinized much more closely as an art medium and taken in with a renewed agency as art, much more so than as a food wrapper or grocery bag that we are trained to ‘recycle.’ I find it fascinating to think that plastic came from fossil fuels that came from ancient living organisms. I hope to help people see plastic in a new way and think of ways to innovate with this material since it will be on this planet for a very long time. Hopefully, we will find a way to cease plastic litter, which is poisoning the planet.”

Northup continues with what he sees as the artist’s role in sustainable practices. “Artists help all of us see our world, our problems, our beliefs in a new way and nudge all of us toward adjusting values and taking action. Artists present problems we typically don’t want to consider in ways we can access and understand; they innovate and inspire us to do the same.”

Not only is Northup giving single-use plastic a second life as art, therefore taking it out of the environment, but he is also contributing to the awareness of the longevity of a resource we use once and then don’t think about again. Northup’s artwork is a visual extension of his activism.

Artists present problems we typically don’t want to consider in ways we can access and understand, they innovate and inspire us to do the same,” says Northup.

Another artist who scavenges for her materials in order to have a kinder footprint on the earth is painter and textile artist

Nicole Young. Young and Northup have both discovered that one person’s trash is a resourceful artist’s medium. Young uses kitchen scraps as well as locally foraged plants to create her paints and dyes.

Avocados, cabbage, onions, black walnuts, Oregon grapes, and so many more options are gathered and cooked with other simple chemicals (like soda ash) and turned into dyes into which cloth is submerged or used as paint directly on the canvas. Says Young, “A big pot of French onion soup is usually followed by bundle dyeing with the onion skins.”

Another reason to reduce, reuse and recycle is cost. In many cases, reducing the amount of materials you use and recycling the materials you have will save you money. Young has come up with brilliant ways to fully flex her creativity using resources that are abundant, low-cost, and readily available.

Young says, “Back in 2013, I wanted to make big, big paintings, but I did not have the money for large quantities of paint. I eventually made the connection that if I wanted to make a big section of my painting yellow, instead of spending $25 on a tub of yellow paint I could spend $2 on a big piece of thrifted yellow fabric and cover the surface with it.”

Young uses kitchen scraps and foraged plant materials to make dyes which she uses to either dye cloth or paint her canvases

You can find swatches of recycled fabric in many of Young’s paintings now. When a scrap doesn’t have a place on a larger canvas, she creates smaller, more affordable works from the waste of the larger ones. Between foraging and repurposing, Young purchases and wastes very little to make her art.

In addition to being environmentally friendly and cost-effective, Young has cultivated an art process that has become a lifestyle that is in sync with nature, something by which she feels profoundly nourished.

“I definitely have a deep respect for nature that I would describe as spiritual. I love rituals; I love being in nature and creating in the way that I do helps me feel connected to nature, the changing seasons, and the world around me. And often when I’m painting, I feel like I’m connecting to something larger than myself.”

Young has created an art practice based on her sustainable lifestyle. Sometimes, in art, there is great meaning to be found not only within the object itself but also in the way it was made. We need people dedicated to a cause to share with us how we can live a life that is authentic to our values.

The challenges of creating sustainable art

However, it’s not always easy or simple to figure out how to live sustainably. Let’s look at farmer, Marymichael D’Onofrio of

Be Golden Farms in Rensselaerville, NY. Marymichael raises a small number of sheep and wanted to make something simple, like a hat, out of their wool. But, as she would find out, just because one has the intention of being sustainable doesn’t mean one has access to all of the necessary resources or skills.

Marymichael insisted that all the vendors she hired would be located in the state of New York. There were companies in China who could make the hats for her, but she didn’t want her hats to have a high carbon footprint and she wanted the money she made in New York to support other businesses in New York State agriculture.

It took Marymichael persistent research and resourcefulness over the course of years to find: a sheep shearer, Siri, from

Yankee Rock Farm; MJ of

Battenkill Fibers, who purchased and restored a 200-year-old mill specifically with the intention catering to smaller local wool producers, a weaver, Hatice from

Simply Knitting Mills, to turn the yarn into beanies; and a seamstress, Mary, who could hand sew Be Golden Farm labels on each hat for a heavily discounted price.

Marymichael says this in conclusion, “After nearly 3 years, five female-run businesses, and starting with just three sheep, I ended up with 96 farm-labeled beanies that never left NY state during their entire manufacturing process for a grand total of $3385.75. This does not include the purchase of the sheep, their food, vet bills, or my time/blood/sweat/tears put into raising them over the past few years which I roughly like to round up to about $3900. I allowed myself to deduct one farm-made beanie for my own personal enjoyment which means the other 95 beanies cost me about $41 a piece to make. All of which I have to pay up front in hopes that I can convince a customer that all of this was worth a $50 beanie.”

Farmer Marymichael D’Onofrio started with 3 sheep and wanted to make a hat out of the wool. The endeavor was costly, time consuming, and taught her a master class in small business operations

Far from a cautionary tale, it’s the mistakes we make which teach us about our own limitations, and the limitations of available resources. This makes it possible for us to focus on what needs to change within our environment in order to achieve sustainability. Now that Marymichael has gone through the process of making beanies from her own wool at what will most likely be a loss, she can figure out how much wool she needs before making a hat that will be profitable. This information is valuable not only to her, but to all farmers in New York State, and especially those in the Hudson Valley.

It takes innovative people to figure out creative ways of working with the resources at hand. The reason I know this is because Marymichael is a vendor at my local farmer’s market, and when she showed up with $50 wool beanies, I had to ask about them. Without the conversation starter of an object, I would not have known about her experience.

Sometimes it’s hard to know how to live sustainably. Understanding what is and what is not a sustainable practice for your life is very important, and it takes a trailblazer to gather the information necessary to make that decision. What helps us learn about difficult topics is stories, and what is art but a story told from a unique perspective?

We are lured in with our eyes, and if we are curious, we ask questions. Some artists make art about sustainability, like Libby Newell and Bryan Northup, and some artists make art by living sustainably, like Nicole Young. In any case, when you support an artist who is promoting sustainability or sustainably made art, you are supporting twofold: the artist and the cause.

What sustainable art have you encountered? Did it inspire you to advocacy or action? How do you incorporate sustainability into your creative practice? Let us know in the comments.