When Dr. Seuss wrote his timeless motivational classic Oh, The Places You’ll Go!, he probably didn’t anticipate that one of those places would be a federal courthouse in Los Angeles. And yet, that’s exactly where he — or, more accurately, the company he left behind when he died in 1991 — has found himself. More precisely, that company, Seuss Enterprises, L.P., recently brought suit against ComicMix, a comic book publisher, alleging that its comic book Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go! infringes on Dr. Seuss’s copyrights and trademarks associated with Oh, The Places You’ll Go!

ComicMix’s book represents what has become known as a “mashup” — an increasingly common practice where fans take elements of two or more popular copyrighted works and put them together to create a new work of authorship. Here, ComixMix combined elements of Dr. Seuss’s original book with elements of the popular television series Star Trek, the title alluding to what was arguably the series’ most memorable line, describing the Starship Enterprise’s mission: “to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

To many, a mashup falls squarely within the bounds of fair use in art — an exception to the exclusive rights granted to authors under the copyright law that permits certain limited unauthorized copying, typically for scholarship, commentary, criticism, and the like. To others, mash-ups represent little more than an unauthorized derivative work that infringes upon the copyright owner’s ability to control how their work is used.

Although this case is not the first time that courts have been called upon to clarify the boundaries of fair use in art, it is one of the few occasions where a court has considered fair use in the context of a mashup so directly. For that reason, this case serves as a particularly interesting and possibly useful guidepost for those interested in producing their own mash-ups.

The Life of a Lawsuit: A Quick Lesson in Civil Procedure

Before we dig too far into this case, it’s important to remember that it came from a district court. The federal district courts are trial courts — the lowest in the judicial system — where judges and juries determine the factual landscape of a particular case and apply the law as appropriate. As the lowest court in the federal system, district court decisions have little impact on the law beyond the dispute (and the parties) immediately before the court in any particular case. Typically when we discuss how courts help shape the law, we look to the appellate courts, known as circuit courts — the next level up — whose decisions are binding on all of the courts within an appellate court’s circuit. In most cases, a “circuit” is a geographic region. For example, New York falls in the Second Circuit while Los Angeles is in the Ninth Circuit. Accordingly, we tend to see a lot of copyright cases come out of those two circuits since many of the major players in the creative industries are headquartered in those cities.

In addition, the decision from the court deals with a motion to dismiss, one of the earliest and most routine types of decisions that a trial court makes in a lawsuit. Generally, a motion to dismiss arises when the defendant asserts that there is no actual legal claim in the plaintiff’s lawsuit, even before either side has had an opportunity to fully evaluate the facts or develop formal legal arguments. In short, decisions on a motion to dismiss are not especially persuasive in future cases.

So why discuss this case at all if it’s not (yet) legally significant? Because as regular readers of Art Law Journal know, fair use cases are heavily fact-dependent, and the decision from the trial court, in this case, offers an especially comprehensive look at how judges think about fair use in art generally and how it might apply in a mashup context more specifically. In other words, no matter how this case ultimately shakes out, we can learn something from what the judge says about fair use in art here.

The Court analyzed whether ComicMix’s use of Dr. Seuss’s work would constitute fair use.

A Fair Use in Art Refresher

To understand the court’s analysis, we must first make sure we understand how the law defines “fair use” in art. As mentioned previously, fair use in art situation occurs where someone is permitted under the law to use a copyrighted work without the authorization of the copyright owner for certain limited purposes such as, in the words of the law itself, “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching … scholarship, or research.” To evaluate whether a particular use is fair, courts use a four-part balancing test that considers:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether the use is commercial or nonprofit;

- The nature of the copyrighted work (published versus unpublished; highly creative versus more fact-based);

- The amount of the work used relative to the work as a whole; and

- The use’s effect on the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work.

Applying the Fair Use in Art Factors

The First Factor

The Court begins, as most courts do, with the first factor: the purpose and character of the use. ComicMix asserts that its mashup, an homage to Star Trek and Dr. Seuss constitutes a parody or satire and that the multifarious cases finding that parody and satire are generally fair use in art should also apply here. But the court disagrees, noting that parody and satires typically use bits and pieces of a particular work to create a new one that comments on or somehow criticizes the original and that there is no such commentary or criticism here. Instead, the court concludes that ComicMix’s mashup “merely uses [Dr. Seuss’s] illustration style and story format as a means of conveying particular adventures and tropes from the Star Trek canon.”

The Court then acknowledges that even though ComicMix’s work cannot be fairly characterized as a parody, “it is no doubt transformative” because it:

combines into a completely unique work the two disparate worlds of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek. Oh, the Places You’ll Go! tells the tale of a young boy setting out on an adventure and discovering and confronting many strange beings and circumstances along his path. Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go! tells the tale of the similarly strange beings and circumstances encountered during the voyages of the Star Trek Enterprise, and it does so through Oh, The Places You’ll Go!’s communicative style and method. Oh, The Places You’ll Go!’s rhyming lines and striking images, as well as other Dr. Seuss works, are often copied by Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go!, but the copied elements are always interspersed with original writing and illustrations that transform Oh, The Places You’ll Go!’s pages into Star-Trek-centric ones.

Finally, the Court recognized that even though ComicMix’s use of the work was no doubt commercial in nature, a factor that typically tips against the defendant, the overwhelmingly transformative nature of the mashup led to the conclusion that the first factor weighs in favor of a finding that this might be fair use in art.

The Second Factor

The Court recognizes that although Dr. Seuss’s mashup is creative in nature, a fact that typically weighs against a fair use claim, the fact that the work was so widely published and highly popular lessens the impact. Accordingly, the court concludes that the factor “weighs only slightly” in favor of Dr. Seuss.

The Third Factor

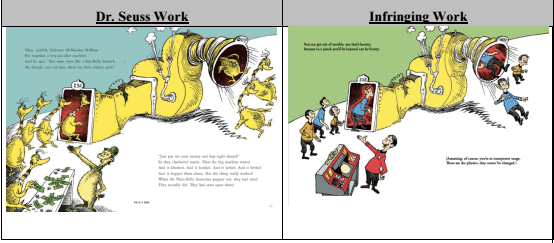

In a typical fair use in art context, the court must consider how much of an underlying work was taken in the course of creating the alleged new fair use work. The Court here, however, implicitly recognizes that a mashup is different, observing that although Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go! boldly (pun fully intended) copies many aspects of Oh, The Places You’ll Go!, it “does not copy them in their entirety,” and that “each is infused with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe the Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint.” Nor does Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go! Copy more than necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose. The court concludes that the factor “does not weigh against” ComicMix, suggesting that the use is fair.

The Fourth Factor

The fourth factor was, at one time, considered to be the most important of the four, though courts have subsequently backed off that somewhat. Still, given that the underlying purpose of copyright law is to provide authors with economic incentives to create, it’s hard to overstate the importance of examining the impact of particular use on the market for the underlying work. Essentially the question the court looks to answer here is whether and to what extent the potential fair use of the work supplants or replaces the market for the original. Put differently, the court must determine whether someone looking for Oh, The Places You’ll Go! might instead decide to buy Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go! The law also requires courts to look at “traditional, reasonable, or likely to be developed” markets, such as licensing markets.

Dr. Seuss’s company asserts that it regularly licenses Dr. Seuss characters, suggesting that it might have done so here and that Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go! essentially harms that market. Critically, the court notes that the record — the body of facts associated with the case — does not contain any evidence suggesting that Dr. Seuss does or does not license his works or what the scope of harm might be (that is, what a license would have cost if it were to grant one to ComicMix). But again, the court points to the highly transformative nature of the use, recognizing that it is “unlikely that Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go! would severely impact the market for Dr. Seuss’s works,” and ultimately concluding that the fourth factor weighs in favor of ComicMix, and suggests fair use in art.

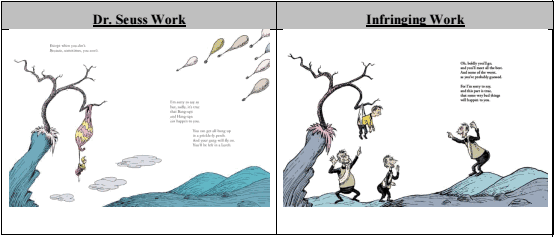

A comparison of Dr. Seuss’s original drawing compared to ComicMix’s mashup.

The Factors: Balanced

Despite the relatively compelling case that the court lays out in favor of ComicMix’s mashup, the court ultimately concludes that because the parties have not had sufficient time to develop the facts with respect to the fourth factor and the otherwise “near-perfect” balancing of the factors, the court denies the motion to dismiss, allowing the copyright claim against ComicMix to proceed.

That doesn’t mean that ComicMix lost the case or even that this case will ever go to trial. The motion to dismiss is simply the earliest opportunity a defendant has to end a lawsuit. The parties will proceed with fact-finding — a process called “discovery” — where each side will have an opportunity to interview each other’s key witnesses and look at key documents relating to the claims. After that process, each side will have a chance to file what’s called a summary judgment motion, which is another expedited way to dispose of a case. Only if the summary judgment motion is denied will the case proceed to trial, and even then, it’s a long shot — the vast majority of cases that make it past summary judgment end up settling out of court.

Some Final Thoughts (and a Reality Check)

This case is interesting and important for two reasons: First, it marks the first time of which I am aware that a court has ever considered a mashup to be in its own category for purposes of the first factor analysis and essentially recognized that a mashup is an important form of creativity that the law should endeavor to protect:

[I]f fair use was not viable in a case such as this, an entire body of highly creative work would be effectively foreclosed. Of course that is not to say that all mash-ups will or should succeed on a fair use defense; the level of creativity, variance from the original source materials, resulting commentary, and intended market will necessarily make evaluation particularized. In this regard, mash-ups are no different than the usual fair use case. However, in this particular case the Court has before it a highly transformative work that takes no more than necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose and will not impinge on the original market for Plaintiff’s underlying work. And the Court is especially mindful that “[i]t would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of [a work], outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.”

Second is the heavy reliance on the concept of “transformative use,” which has become a staple of fair use in art cases in recent years. What was once considered just a part of the first-factor discussion has become, essentially, the sole test for determining whether a particular use is fair. Many courts, such as the one here, walk through the four factors but ultimately rely on the degree of “transformativeness” as the basis for their conclusions in each of them. This trend toward collapsing the entire fair use in art analysis into a single factor has been frustrating many copyright lawyers for some time now, and this case offers further evidence of the current course of the law. How the appellate courts will deal with these issues in the future remains to be seen.

And that reference to appellate courts offers a good opportunity to remind us of an important point: the case discussed here is in its infancy, and the opinion described here is of very little jurisprudential weight. At least for now. It’s possible that the case will work its way through the system and mature into an appellate decision that will have the weight of law in the Ninth Circuit (where the Central District of California resides). Far more likely, the case will settle, leaving us with this glimpse of judicial insight into the mashup and the applicability of the fair use in art doctrine. So stay tuned.

Do you think ComicMix’s mashup should be considered fair use in art?