Given the number of forgeries circulating in the market, authenticating art has become a booming business. Collectors investing in artwork from emerging and established artists face a significantly greater chance that the artwork they have purchased is fake. According to the Fine Art Expert Institute (FAEI), 50 percent of art circulating on the market is forged or misattributed.

That may seem like a high number, but just head over to eBay to see how many signed Lichtensteins or Rothkos are selling for under $150. The problem is compounded when the estates of iconic figures like Warhol, Haring, or Basquiat will no longer authenticate their works.

Unfortunately, the forgery problem isn’t isolated to merely inexpensive work sold online but has also affected major institutions and museums. For instance, the Étienne Terrus Museum held a dedicated showing for Étienne Terrus, with 140 pieces of his art up for viewing. It was later discovered that almost 60% were fake.

Jorge Perez, a Miami real estate developer, made quite a splash when he donated $35 million in cash and art to build Miami’s new flagship museum, the Perez Art Museum Miami. Most of the works donated were early pieces from established Latin American artists, like Wilfredo Lam and Antonio Berni. However, the entirety of the museum’s collection was called into question when it was discovered that a painting by Cuban artist Carlos Alfonzo donated by Mr. Perez to the Frost Art Museum In Miami, was a forgery.

This work, assumed to be by Cuban Artist Carlos Alfonzo, was deemed a forgery.

Perez stated he was “shocked,” claiming that none of the visitors to his home, nor many leading art experts well acquainted with the artist, ever noticed anything amiss about the painting in the 16 years that it hung there.

What could Mr. Perez have done to ensure the work was authentic and what are the consequences for the seller if a work is later revealed to be a forgery? If the seller was also duped, would the buyer have any recourse?

When purchasing artwork, especially ones that have significant value, a buyer or collector should take steps to verify that the work is authentic. Relying on the seller’s word or personal knowledge may not be enough. After all, anybody can print a “Certificate of Authenticity,” but without the proper documentation to back it up, you might as well use it as starter paper in your fireplace.

Tips for Authenticating Art

In an ideal world, one could simply hire an appraiser to verify an artwork’s authenticity. Unfortunately, there isn’t an abundance of qualified art appraisers available in the United States, and many are so specialized that finding one to suit your needs can be challenging. In some states, such as New York, the process is a bit easier since they have instituted laws requiring auction houses and galleries to certify the works they sell as authentic.

However, before looking for someone to authenticate art, there are several things you can do on your own.

Provenance

Art experts use several different methods to authenticate art, the most important and common being provenance or the documented ownership history. Establishing provenance can be done in a variety of ways, including:

- A signed certificate or statement of authenticity from a respected authority or expert on the artist.

- An original gallery sales receipt or receipt directly from the artist.

- An appraisal from a recognized authority or expert on the artist.

- Names of previous owners of the art.

- Newspaper or magazine articles mentioning or illustrating the art.

- A mention or illustration of the art in a book or exhibit catalog.

- Verbal information is related to someone familiar with the art or who knows the artist and who is qualified to speak authoritatively about the art.

If provenance is firmly established by an authorized expert or auction house, then the work is likely authentic.

Signature

To determine if the signature is likely from a particular artist, you should first access other works by the artist to get a feel for the signature style and placement. Is the signature placement consistent? Do the signatures of other works have variations? Is the signature on the work you are authenticating different from the ones on other works?

It may be helpful to turn the signature upside down. This way, your mind isn’t reading it and can look objectively for tell-tale signs and slight differences.

Make sure the signature is added by hand. Use a magnifying glass to see that it is actually painted or, if it is ink, that it is imperfect. If the signature is added by a printer or other device, like an autopen, a device used to mimic inked signatures. Printers will have perfectly filled-in lines, and an Autopen, or other similar devices, will usually have a small dot at the beginning of the signature where the pen is placed onto the paper by the machine.

Also, hand signatures will have density variations caused by pen pressure when signing. Printed or automated signatures will be more uniform. Try holding the signature up to the light to see if some areas are easier to see through than others.

Any mismatch should be a signal to doubt its authenticity.

Print Quality

Fine art prints usually use a higher quality process than inexpensive prints. Giclée prints, for example, use a high-resolution inkjet printer with a much higher density of ink droplets than a traditional printer. Use a magnifying glass to view a typical print and compare that to the artwork you are interested in purchasing. a Giclée should be smoother and denser, with fewer spaces between the ink droplets.

Other printing processes, such as lithographs or screen printing, use ink placed on etchings, which are then run through a press to create the image. The press creates an uneven surface that you wouldn’t see with a cheap print or even a Giclée. If the print is a limited edition, you will often see the edition number printed on the work. These numbers are usually added by hand after the printing is completed, so check to see if those numbers were made by hand and not printed.

Certificate of Authenticity

A Certificate of Authenticity is a signed document with details about the work, signed by the artist or representative. The certificate is usually issued with the original sale (I.e., from a gallery) and should be passed down to each owner as it is sold. Although there are many reasons why an artwork would not have a Certificate of Authenticity, but the absence of a certificate should be a reason for concern.

Unfortunately, a Certificate of Authenticity is easy to fake. If you are purchasing the artwork from a reputable gallery, the Certificate is likely to be genuine since the ramifications of forging a certificate or faking the authentication wouldn’t be worth it to the business. If the work is a resale, you should consider contacting the artist or organization that issued the certificate to ensure it is genuine.

Hire an Expert

There are other methods to prove a work’s authenticity, but they are much more complex and would require hiring an art appraiser or authenticator. For example, a conservation and technology report uses scientific analyses to determine the present condition of the artwork, the history of any intervention concerning the condition, and what alterations have been made. This type of analysis is particularly helpful for old masterpieces since many of the above-mentioned grounds for authentication are impossible to trace beyond a certain time frame.

Unfortunately, even hiring an expert appraisal comes with risks.

The Difficulty for Art Authenticators in Today’s Market

Finding someone to authenticate your work is becoming increasingly difficult, as many art experts and authenticators are concerned with the threat of litigation. Authentication is not exact, and even the best appraisers can be wrong. For example, a long-lost second version of Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio turned up in an attic in France. After some research and analysis by Caravaggio expert Mina Gregori, the work was claimed to be fake. Then, Eric Turquin, another Carravagio expert, authenticated the painting and valued it at €120 million. The painting is still under controversy.

When a buyer or seller is likely to lose money due to mistaken authentication or even a well-thought-out opinion denying authentication, lawsuits are inevitable. Resolving these disputes isn’t always easy and has made it harder to authenticate work.

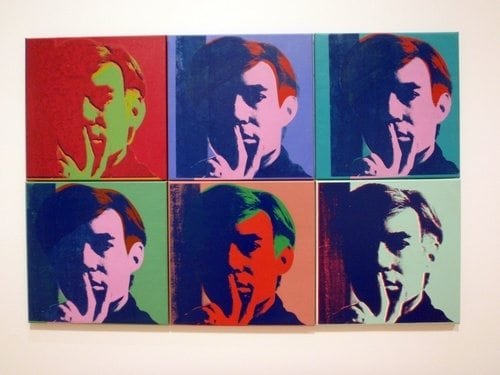

Works like this set of Six Self-Portraits by Andy Warhol (1967) will no longer be authenticated by the Warhol Foundation due to the risk of excessive lawsuits.

In response to a plethora of litigation, many art experts and art authentication committees have altogether stopped giving opinions on works of art, citing the risk of litigation and its accompanying costs far too great to support the risk.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, the Keith Haring Foundation, and the Noguchi Museum have all stopped authenticating works to avoid litigation. Others have taken increased precautions by imposing contract terms to avoid any liability when authenticating works.

For example, many committees’ contracts include clauses prohibiting the collector from suing a committee if they reject the work’s authenticity. Since a work rejected by a committee typically has no commercial value, a buyer is left with virtually no avenues for recourse.

Recognizing that a lack of art authentication can seriously affect the art market, New York’s legislators have taken steps to protect authenticators and committees.

State Senator Betty Little stated, “Art authenticators are critical to preventing art forgery and fraud. However, very expensive lawsuits have deterred these experts from rendering their opinions to the point of disrupting commerce. The point of this legislation is to establish protections under the law to ensure that only valid, verifiable claims against authenticators are allowed to proceed in civil court.”

This may lead to increased availability of authenticators and appraisers in the future, but the reduced risk of litigation could also give rise to a market of authenticators with minimal credentials or expertise. The effect this law would have on the market remains to be seen.

Regardless, the risk of litigation today has led to an increasingly prevalent market of Warhols and the works of other artists without any means to authenticate them. We have all heard the term “buyer beware!” Given the purported number of forgeries out there, that statement has never been more true for art buyers and collectors.

Are you an art collector? Does the lack of certainty in authenticating art make you nervous about buying art? Let us know in the comments.